Public Attitudes about the End of the Public Health Emergency: Framing the Consequences

On May 11, the national Public Health Emergency (PHE) declaration by the federal government will end. While this event has major public health implications, broader media and public attention to the event has been limited, likely because at least half of Americans earlier this spring reported that they believed that the pandemic was already over.

With relatively limited available information about public sentiment toward the official end of the PHE (or public understanding of its implications), our COMM HSP team was curious to understand public support or opposition for this milestone, as well as whether framing this event to emphasize its public health consequences might shape the public’s views.

What We Did

We fielded a short survey experiment from March 30 to April 3 using the AmeriSpeak Omnibus, a bi-weekly survey administered by NORC. We randomized half of the 1002 nationally-representative participants to receive an “informational” survey item that simply provided a statement about the end of the pandemic emergency: “On May 11, 2023, the national COVID-19 Public Health Emergency will end.” The other group received additional information that emphasized two of the most salient consequences of the declaration’s end – loss of free COVID-19 testing / treatment and the end of some beneficiaries’ Medicaid insurance. This “consequences” survey item read: “On May 11, 2023, the national COVID-19 Public Health Emergency will end, which means some people could lose their health insurance and COVID-19 tests and treatments will no longer be free.” Both groups were asked to respond to the question: “How much do you support or oppose the decision by the federal government to let the public health emergency declaration end?”

What We Found

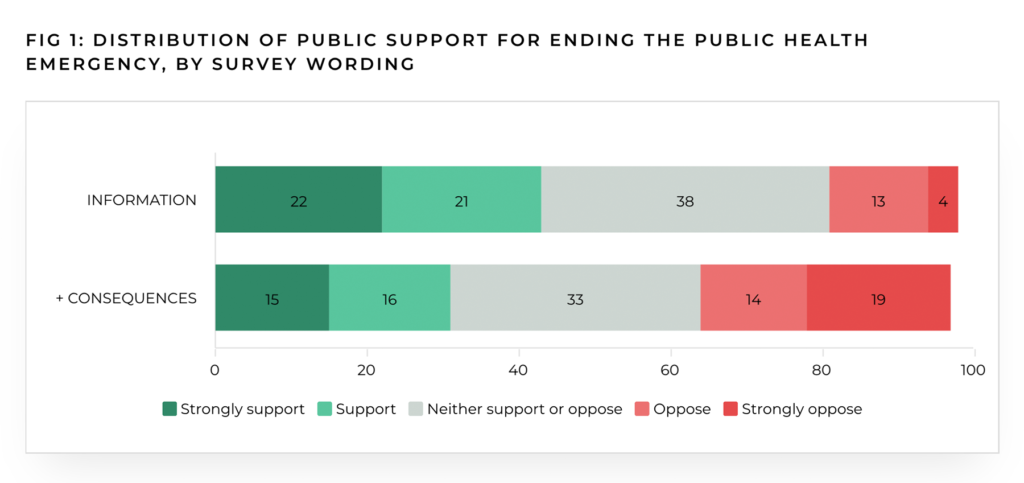

Figure 1 below demonstrates the differences in survey responses based on this framing. Among those that did not receive the consequences information, most people were supportive of or neutral toward the emergency ending (43% supported, 38% neutral, and 17% opposed). However, once made aware of the consequences, support decreased, and more people shifted toward opposition (31% supported, 33% neutral, and 33% opposed). There were particularly notable differences between the two survey versions for those with strong views: the proportion of those strongly opposed to the end of the PHE was only 4% for the simple information condition and 19% for the consequences condition.

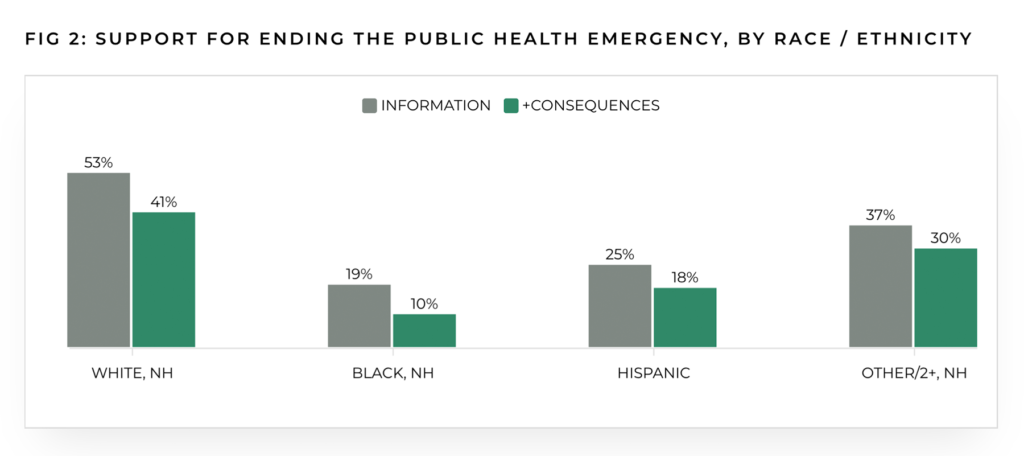

Exposure to the consequences language had a similar effect on all racial and ethnic groups, with lower support for the emergency’s end for all groups compared to the simple information language, as shown in Figure 2. However, there were substantial racial differences in overall support for the end of the PHE. For those who received the simple information, 53% of White respondents supported the end of the emergency, while only 19% of Black respondents did so. This finding indicates salient racial differences in support for the role of federal policy in protecting and mitigating harm from COVID-19, which would particularly benefit lower-income people and people of color. Another national poll conducted around the same time as ours also found Black and Hispanic people were more concerned about the impact of the end of the PHE compared to White people. As the PHE ends, so too ends at least part of the federal government’s role in distributing resources in ways aligned with promoting an equitable response.

Implications for Communicators

On May 4, 2023, the Public Health Communications Collaborative issued messaging guidance for public health departments and other communicators about the end of the PHE. The guidance recommends that all communicators emphasize that the end of the PHE does not mean the virus is no longer a threat to public health. They also emphasize that COVID-19 vaccines will continue to be free, but – similar to the content of our “consequences” survey wording – that COVID-19 tests will no longer be available free of charge to most Americans. Our findings from this public opinion experiment suggest that when communicators emphasize these public health implications, such a message does garner the public’s attention.

Read more related work from the COMM team:

- On the content of 2020 federally-affiliated COVID-19 public service announcements

- On local TV news coverage of racial disparities in COVID-19

- On Americans’ perceptions of COVID-19 disparities in 2020-2021

This survey was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant no. 79754). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.