“Do These Reminders that Disparities Exist Even Do Anything?”

A Practitioner-Grounded Research Agenda on Communication and Health Equity

Report on Listening Sessions with Four Types of Communicators in Practice, June 2024

- Browse the Report

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- What We Did

- What We Found

- — Questions about Media Effects or Public Opinion

- — Questions about News Media Content

- — Questions about Journalistic Practice

- — Needs and Resources

- — Research Dissemination Preferences

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- References and Endnotes

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Communicating about health equity has become increasingly challenging, as the political and communication landscapes have shifted since the public reckoning with racist systems in 2020. To understand the major research needs communicators face in this context, the Collaborative on Media & Messaging for Health and Social Policy conducted semi-structured interviews with 36 practitioners in late 2022 and into 2023. Interviewees were drawn from four groups: communicators from public health organizations; individuals with communication roles from advocacy, organizing, or narrative change sectors; practicing journalists in print, television, and print outlets; and thought-leaders with experience communicating about health equity-related topics to mass audiences. This report describes the research-related questions these communicators raised, their information or evidence needs, and how they prefer to receive research. The interviews reveal an urgent need for additional research and a bold agenda, ripe for academic and non-academic researchers to fill, consisting of four areas:

- Research questions about media effects and public opinion

- Examples of such questions include understanding public perspectives on racism and how strategic messaging can influence the public’s perspectives without contributing to further resistance.

- Research questions about media content

- One example question concerned what sources are included in stories related to health equity, and whether community expertise was valued.

- Research questions about journalistic practice

- Questions included increasing trust in media within communities of color, and understanding differences in coverage of health equity topics across non-profit or community-centered outlets versus mainstream outlets.

- Providing needed infrastructure to share research and other resources and align and coordinate communicators across sectors

Communicators serve an important function in shifting narratives and creating the conditions for policy change, and they need more resources and evidence to guide their work.

Additional research and coordination is needed to fill these research gaps to support communicators in their critical work, with the following key recommendations:

- Accessible and Applied Research Delivery: Deliver research in accessible and applied ways. Academic research should include practical applications to ease the burden on practitioners who need to apply findings to their work. Make research open access to ensure wider availability.

- Clear, Concise, and Engaging Formats: Disseminate research through formats that cut through information overload. Use toolkits or messaging guides, keeping documents concise (ideally under three pages) with links for deeper exploration. Visually appealing infographics can enhance accessibility and memorability.

- Integrated and Synthesized Research: Provide synthesis of findings across multiple studies to show how they can be applied to practice. E-newsletters summarizing relevant research can be valuable, especially if they come directly to practitioners’ emails.

- Utilize Existing Channels: Disseminate research through existing channels that communicators already use, such as podcasts, tables of contents from journals, and professional associations.

Introduction

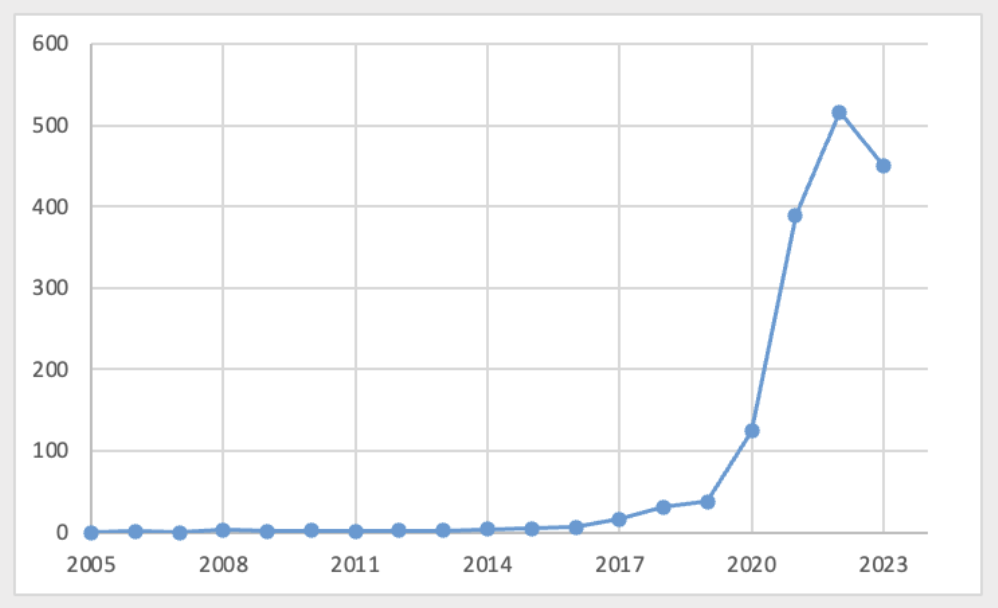

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 in the context of the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to unprecedented attention to racial health inequities in public discourse. For instance, one study examining print news coverage of COVID-19 between January 2020 to September 2020 found that a substantial proportion of coverage (about 39%) reported on racial/ethnic disparities in cases and deaths.¹ By 2023, 265 states, cities, and counties had made declarations that racism is a “public health crisis”.² This increase in attention to the connections between racism and health was also evident among the scholarly community, with medical research on the topic accelerating following 2020 (see Figure 1 below).³ All of these trends contributed to a greater availability of information about health inequity in the broad communication environment.

Figure 1 – PubMed Search Hits for “Structural Racism” and “Health”, 2005-2023

Source: Authors’ searches of PubMed (National Library of Medicine) on March 18, 2024. Search strategy modeled after Dean and Thorpe (2022).³

However, at the same time, the communication environment became increasingly challenging after 2020, with active and organized opposition to some concepts related to diversity, equity, justice and antiracism advanced by elected officials, high-profile commentators, and well-resourced interest groups.⁴ Even before these concepts became overtly politicized, public understanding of these issues was middling at best.⁵

These conditions have put communicators in a difficult position. How should communicators talk about issues of health equity, and racial inequities in particular, in this context? What information or evidence might help communicators be better prepared to face the communication challenges in light of the climate of 2024 and beyond?

Our Collaborative on Media & Messaging for Health and Social Policy research team sought to understand the unique challenges that communicators face, as well as what questions they most struggle with that research evidence might begin to address. We also wanted to find out how communicators in practice might best access and make use of relevant communication-related research evidence, were it to be available.

We included four types of practitioners who communicate about health and racial equity⁶ in our study:

- communicators in public health-specific organizations (government, non-governmental organizations, and health philanthropies);

- people who do communication in social change-related organizations (power-building organizations, organizations engaged with narrative strategy, advocates);

- practicing journalists at television, print, or online outlets;

- thought-leaders who are not professional communicators or practicing journalists but who have real-world experience in communicating about health equity to constituencies or mass audiences.

We interviewed 36 practitioners to understand the strategies they are using to get their messages about health equity across, the barriers they face, the resources they rely on, as well as the specific needs they have for research and how they would want resources and research shared back to them. Our objective in this report is to summarize the research questions posed and dissemination preferences described across these four groups. (We will report on the strategies and barriers in a separate publication.) We consider these four groups of practitioners as the potential end-users of research evidence to inform their communication approach and strategy research.

The goal of this report is thus to share research gaps and research needs to build a communicator-centered research agenda, so researchers – including those in academic and non-academic settings – who tackle these issues can be guided to the questions that most urgently require answers according to those in communities of practice.

What We Did

Between November 2022 and May 2023 we invited individuals spanning the four categories of practitioners and leaders via email to participate in interviews about the topic of communication and health equity. We started with a small number of people identified in each of the four groups, based on the study team and funder contacts, and then asked participants to suggest others whom they thought would have important perspectives.

Our initial target was at least eight participants in each of the four categories, and we purposefully sought variation to achieve diverse perspectives. For instance, within the public health practitioner group we included people affiliated with state and local governmental public health agencies, as well as national and local public health non-profits and philanthropic organizations. Within social change advocates, we included non-profit health advocacy organizations, power-building organizations, and people whose roles included narrative strategy. Within the journalist category, we sought out interview participants from mainstream print, online, and television journalism. Finally, for thought leaders, we sought out people whom we identified as leaders in diverse health equity contexts as well as former journalists who now occupy leadership roles related to communication. Across all four categories, we purposefully recruited to achieve racial, ethnic, and gender diversity (and to a lesser extent, geographic diversity) among the individuals invited, as well as variation in the fields and communities (e.g., Black, LGBTQ+, Indigenous communities) with which they work. In total, 36 people participated in the interviews (see Table 1). Per our Institutional Review Board approval and agreement with all participants, we do not include identifying information.

Table 1 – Interview Participants

| Role | Number |

|---|---|

| Public health practitioners and philanthropy | 13 |

| Advocates and narrative change strategists | 8 |

| Journalists (active) | 8 |

| Thought leaders, including former journalists | 7 |

Interviews were scheduled based on the interviewee’s availability and were conducted between November 15, 2022 and August 2, 2023 with one of two leading members of the research team, with research assistant support in each interview. We used a semi-structured interview guide as an outline for the conversation. All interviews were conducted over Zoom and ranged from 30 minutes (at the interviewer’s request) to one hour and were transcribed verbatim through an AI-assisted live transcription service. After each interview, the lead interviewer wrote up 2-3 pages of field notes for each interview across defined categories. Then, field notes were inputted into Dedoose software, the team co-developed a coding scheme using an iterative process, and the codebook was applied to all field notes. For this report, we do not generally break out differences by participant role, except where noted.

What We Found

About our Participants

The roles of the 36 participants are displayed in Table 1. Twenty (56%) participants identified as Black, Indigenous, or other person of color, while 16 (44%) identified as White. Fourteen (39%) identified as men, 21 (58%) as women, and 1 (3%) as non-binary. Most (28, or 78%) reported having at least some kind of formal or informal training in communication (e.g., a communication course or degree; media training workshop; or journalism training). A similar proportion (27, or 75%) reported at least some kind of formal or informal training in public health with a health equity focus.

Research Questions

Participants identified many important research questions. These questions spanned four categories: (1) questions about media effects on the public or of understanding the public’s (or population segments’) perceptions; (2) questions about news media content; (3) questions about journalistic practice; and, (4) other needs or resources required to advance practitioners’ capacity or knowledge-base. Tables 2 through 5 display these categories of questions and specific examples. Below, we illuminate these questions with a few illustrative quotes.

Questions about Media Effects or Public Opinion

Six sets of research questions emerged related to media effects and public opinion (see Table 2). These included questions about how the public understands racism or responds to communication about racism; questions about communication strategies about racial and health equity; questions about a community-centered approach to understanding communication effects, such as on Black, Indigenous, and people of color specifically; questions about the positive or negative effects of communicating disparities data in risk communication; questions about communication about politicized topics in a polarized mass public; and questions about science communication in contexts of conflicting science and misinformation. Quotes capturing some of these ideas are below.

For instance, on the impact of messaging about disparities, on different audiences:

(Governmental public health leader, #12)

(Journalist for online outlet, #50)

(Governmental public health leader,#48)

Others discussed the need to develop messages that clarify and advance public understanding of structural racism, and also avoid contributing to resistance:

(Non-profit public health leader, #02)

(Print journalist, #08)

Others talked about how more research is needed on expansive communication strategy, to bridge and engage people across multiple health equity issues:

(Health advocacy leader, #32)

Finally, another important theme was the need for more research on how to communicate about science to build trust:

(Public health leader, national non-profit #33 _49)

Table 2 – Research Questions Elicited from Interview Participants: Media Effects or Public Opinion

| Category | Type of Question | Specific Question |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions about media effects and public opinion | Public opinion about or communication about racism | To what extent does the public understand structural (as compared to interpersonal) racism? Does the public understand the link between structural racism and health? |

| What communication approaches can promote a better understanding of the existence of structural racism? | ||

| How do different groups (such as younger or older, within- and cross-racial groups) respond to messages about racism? How are mindsets and beliefs related to equity different within and across groups? | ||

| Communication or messaging about health and racial equity | Does making the explicit connection between a social policy area to health and health equity advance racial equity goals? | |

| What messages can overcome cynicism or fatalism that change is even possible? | ||

| What terminology should be used to describe specific marginalized groups? | ||

| What storytelling strategies best convey the broad context while still engaging audiences and not promoting individualized understandings? | ||

| What alternative narratives that focus on positive values and vision most effectively shift mindsets and beliefs toward health equity? | ||

| What communication strategies about social policy are needed to positively promote policy instead of reifying stereotypes of recipients of the social safety net? | ||

| Community-centered communication | How does communication about inequity and racism affect those within affected communities? What narratives about health equity do those most affected want to see lifted up? | |

| What does a Black-centered research agenda about communication look like? What archetypes, values, and political narratives circulate within Black communities and affect how they see the world? What narratives must be shifted among Black Americans to yield support for reparations or other forms of structural change? | ||

| Disparities data and risk communication | How do messages about disparities (i.e., group Y is worse off than group X) affect both groups in the comparison? Does highlighting disparities lead to unintended consequences? | |

| Polarization and politicization | What communication strategies related to health equity can overcome partisan divides, and reach people who are not already on board with health equity as a goal? What strategies can avoid backlash or alienation on either side? | |

| How do we communicate about the importance of public health (and of government authority) in a post-COVID, politicized, public health context? | ||

| Who are the trusted communicators about public health in the polarized climate; which types of sources can best bridge divides? | ||

| Other science communication issues | What are the best ways to communicate about the evolution of science (i.e., that science is a process that evolves)? What communication strategies can boost trust in science? | |

| What are the best ways of combating misinformation? | ||

| What is the public’s media literacy, and how does the public’s engagement with media differ across different linguistic or cultural subgroups? How has health information-seeking changed over time? |

Questions about News Media Content

Three general areas came up related to research questions about media content: questions about COVID-19 news coverage, questions about coverage of health equity issues generally, and questions about whether the media covers asset- or strength-based depictions of communities of color and other marginalized populations. See Table 3 for specific questions.

For instance, participants wanted to know to what extent COVID-19 news coverage made connections to racial inequities and how health equity issues are framed. Others were interested in the extent to which news media elevated community-based and lay-public expertise about health equity among those most affected, relative to institutional sources of expertise like public information officers. Others were interested in how health inequities are framed in terms of data, stories, and asset-based or strength-based narratives. Quotes capturing these ideas are on the following page:

(Health equity advocate #34)

(Journalist on local TV, #41)

(Journalist on national online outlet, #17)

(Governmental public health leader, #6)

(Philanthropy public health leader, #26)

Table 3 – Research Questions Elicited from Interview Participants: Media Content

| Category | Type of Question | Specific Question |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions about media content | COVID-19 news coverage (specific) | What sources were cited for their expertise? |

| How was the vaccine roll-out covered? | ||

| To what extent and how was COVID-19 covered in reference to racial equity? | ||

| How has disability been covered in the context of COVID-19? | ||

| To what extent was the news a source of COVID-related misinformation? | ||

| Coverage of health equity issues (general) | What sources are cited for their expertise? | |

| How does coverage of health equity differ across the U.S.? | ||

| How do news institutions reflect systemic racism in the ways they cover (or not) equity issues? | ||

| What frames are used in covering issues of equity (e.g., use of data to identify disparities; systemic or structural, versus individual explanations; connection to social determinants of health; emphasis on mistrust) | ||

| How have counter-narratives (e.g., “CRT” “anti-woke”) been covered? | ||

| How and how often are underrepresented populations covered, and is this done in stigmatizing ways (i.e., disability, Black, Native American communities, LGBTQ+)? | ||

| Asset or strength-based depictions | How and to what extent do the strategies advanced by organizers or narrative strategists (e.g., focus on values, strengths, positive vision) get diffused into news media? | |

| How often are strength-based or asset-based frames used by media in practice? | ||

| How often do news media cover solutions versus problems? |

Questions about Journalistic Practice

Four sets of questions emerged related to journalism practice (see Table 4). These included the need to study the journalism workforce, examine the structural oppressive issues within news media, and understand diversity across journalists and news outlets, including a focus on non-profit and community-centered journalism. Others discussed identifying opportunities for reporting to increase trust and combat the negative news narratives that participants said contribute to distrust and cynicism among audiences.

Other questions concerned diversifying the sources that journalists rely on as well as focusing on not just the effects of verbal content, but also of images in stories about health equity.

Salient quotes below identified the examined the need to explore structural issues related to how mainstream news may profit from coverage of health equity, and how the news itself can be a vehicle of oppression.

(Community thought leader, #11)

(Governmental public health leader, #28)

Others noted that research must explore how the news should be a more consistent source of public health information, and not only in a crisis, and that the news should spend more time portraying positive assets of communities.

(Public health leader, national non-profit #33 & #49)

(Community thought leader, #54)

Table 4 – Research Questions Elicited from Interview Participants: Journalism Practice

| Category | Type of Question | Specific Question |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions about journalism practice | Diversity of journalists, journalism outlets, and approaches | How do community-focused or ethnic-targeted news outlets cover health equity issues compared to major news outlets? What drives research institutions to get coverage in mainstream or major news outlets compared to smaller? |

| Do audiences seek more service-oriented or solution-oriented journalism? | ||

| What is needed to prepare the journalism workforce to address health and racial equity issues, and how can journalists of color be equipped with resources? What resources are needed to support Black journalists specifically? | ||

| What are the implications for content of stories and audience interest when journalists who are white and not from the communities affected cover health and racial equity issues? Versus when journalists are attached to the affected communities? | ||

| Increasing trust and combating negative narratives | How can trust in health journalism be built and maintained perpetually, and not only considered in crises? | |

| What interventions are needed to boost support for and trust in journalism and journalists, especially among marginalized communities? | ||

| How can negative news narratives about communities be combatted, and what is the impact of continued exposure to harmful narratives? | ||

| Sources | What resources are needed to ensure journalists have access to diverse sources? | |

| Images | What are the effects of images used in covering communities of color on audiences? |

Needs and Resources

Besides the specific research questions described above, many interviewees also identified additional needs or resources that would help support their own communication as well as bolster the ability of the communication workforce to reach audiences effectively with information about health equity. Table 5 describes these priority areas: education or training, alignment and coordination of communicators, creating platforms for sharing research and communication tools, developing lists of sources and diverse experts, and specific needs for focused dissemination of research.

Education and training needs spanned many types of learners, including public health students; journalism practice internships for students to bolster smaller non-profit newsrooms; educating and training for news media producers (journalists, as well as editors) about framing as well as about racism and misogyny; supporting thought-leaders with training on social media and protection from pushback; and creating a more racially-diverse pipeline of narrative change practitioners.

(Journalist, #8)

Another key theme was the need for more strategic coordination of the main players in the various communities of communication, advocacy, and narrative change. Interviewees spoke in some depth about the challenges of fragmentation and duplication, with so many groups funded in spaces surrounding social justice communication. They suggested that more investment in convening the multiple groups and coordinating the sharing of resources would go a long way toward building a stronger and less fragmented community of communication practitioners.

Alongside this request was the articulated need for the creation of easy-to-access platforms. Interviewees suggested there was a need for shared resources (sometimes described as “portals” or “clearinghouses”) to track what messages and narratives are being used as well as to store and share messaging resources, including research and evidence-based toolkits and messaging guides.

(Narrative change/advocacy leader, #37)

(Public health non-profit leader, #3)

(Narrative change/advocacy leader #25)

Among journalists in particular, interviewees described the need for creating and sharing expert lists on health-related topics that are inclusive of community-based expertise, and not only institutional experts (at universities or public information officers). Journalists wanted to draw upon such resources when sourcing stories about health equity, to be able to find diverse voices to center in their reporting. Another important dissemination need that emerged from the interviews was for the results of communication and narrative research (such as promising and evidence-based messaging guides surrounding communicating about racism) to reach journalists, specifically. They noted that journalists are not often the audiences of such research. Other interviewees, largely from the public health sector, discussed the need for more strategic dissemination of health communication research to communicators in local, state, and national health departments as well as other partners in non-profit organizations.

Table 5 – Research Questions Elicited from Interview Participants: Needs and Resources

| Category | Type of Question | Specific Question |

|---|---|---|

| Other needs, resources, or training | Education or training needs | Training of public health students and public health researchers in communication, media engagement |

| Need more training and internships for journalism or public health students in smaller community-focused newsrooms | ||

| Need more education of editors about racism and misogyny and also about framing | ||

| Thought leaders speaking out about racism need more support in social media and protection from threats | ||

| Diversifying the fields of practice of communication and narrative work to avoid a research base “grounded in whiteness” | ||

| Alignment and coordination | Need more coordination of key players in the “ecosystems” of narrative infrastructure and health communications | |

| Investment in narrative infrastructure | ||

| Promotion of sharing of resources and coordinated toolkits and messaging resources, to avoid duplication and fragmentation; alignment of grantees working in similar spaces | ||

| Create platforms for sharing research and tools | Create databases for identifying and finding narrative and applied communication research results, i.e., a clearinghouse to identify research and how it can be applied | |

| Resources for identifying what myths, misconceptions, or counter-messages are trending in a population | ||

| Sourcing lists and resources | Create and disseminate diverse lists of sources and a wider set of experts, including training those individuals to better understand media norms | |

| Dissemination needs | Strategic dissemination of results of narrative change research and messaging research to journalists | |

| More sharing of health communication research to public health practice, including health departments |

Research Dissemination Preferences

Most, if not all, interview participants recognized that research could have value in supporting their communication practice, but they had a range of preferences about how to receive this. While there was no uniform set of preferences on specific ways to disseminate research (either within or across the four groups), there was consensus that research should be delivered in accessible and applied ways. Some commented that academic research does not go far enough to explain how exactly research can be put into practice, which places the burden on practitioners to apply relevant findings to their work – costing them valuable time and resources they often do not have. Few practitioners can access academic communication science research as much is behind paywalls at academic journals. Some interviewees noted that they rely on particular individuals whom they know (such as through Schools of Public Health) to access research that lies behind a paywall. Many commented that research must be open access, so more people outside of academia can have access.

At the same time that interviewees valued research, many noted that they already receive so much information, so research dissemination has to “cut through the noise” (as a public health leader noted). All types of communicators have email-overload, and so for research to stand out, its applicability and usefulness must be clearly identified.

Many commented that a toolkit or messaging guide would be the best way to share communication-related research, highlighting exactly how it can be applied, with links or accompanying reports or articles for those who want to dig deeper. As one narrative change leader noted, “If it’s more than three pages, people aren’t going to use it.” Others noted that visually appealing infographics can help to make research accessible and memorable. In addition to clearinghouses or resources to store and share research as described above, others noted the importance of synthesis – efforts to integrate findings across multiple studies and explain how they can be applied to practice. Some noted the value of e-newsletters that come directly to one’s email and offer multiple summaries of relevant research.

Respondents differed on the specific vehicles through which they would want to receive relevant research. Some noted they would prefer (likely because they receive so much information already) to get relevant research through existing ways they already access research – such as podcasts they already listen to, tables of contents from journals, or resources shared through existing groups. Groups that some cited included Rad Comms, the Public Health Communication Collaborative, Columbia Journalism Review, and professional associations (like, for journalists, the National Association of Black Journalists). Journalists noted that a specific presentation for newsrooms to learn about research would have value. Still, others would appreciate other types of presentations that share specific research findings, with a focus on how they can be put into practice in practical workshop-style sessions. Many noted that they see a lot of research shared in webinars, but some noted fatigue with webinars. Webinars put on by organizations the interviewees are already paying attention to (such as the Center for Health Journalism at USC) would have appeal.

Media and social media were also cited as mechanisms to learn about new research. Many noted that they would pay attention to research shared on social media, although interviewees noted some skepticism regarding social media given changes taking place in the ownership of Twitter / X and difficulty staying up to speed with other types of social media outlets like TikTok. Others noted that when research is covered by major media outlets, that is one way that they learn about it.

Last, some people noted that personal outreach and relationships are important. Interviewees noted that they are interested in research that is shared by specific people that they know and are in relationship with; but this also extended to “influencers” – people sharing research whom they may not know personally, but whom they trust in the health equity space. (For example, people identified in this category were Dr. Uché Blackstock and Dr. Aletha Maybank). Receiving research within the context of established partnerships (such as an academic partnership with a public health organization) was also identified as an effective opportunity to share research. Some journalists and public health leaders alike commented that there was a great opportunity to develop these partnerships between researchers and journalists. One thought-leader (from a non-profit news vantage point) commented that researchers should be engaging with journalists much earlier, throughout the whole research process, which can build relationships both with the journalist as well as the community that is the focus of the work, and create the opportunity for more use of the eventual findings.

Conclusion

Interview participants identified a multifaceted research agenda, illuminating research needs for interdisciplinary researchers both inside and outside of academia. Core research needs were clustered across four areas: (1) research questions about media effects or public opinion, such as understanding public perspectives on racism and how strategic messaging can influence the public’s perspectives about health equity without contributing to further resistance; (2) research questions about existing or past media content, such as what sources are included or highlighted in health news stories related to health equity; (3) research questions about journalistic practice, such as increasing trust in media within communities of color and understanding differences in coverage as well as news coverage effects across non-profit / community-centered outlets versus mainstream outlets; and (4) providing needed infrastructure to share research and other resources and align and coordinate communicators across sectors.

Funders and organizations working at the intersection of communication and health equity should consider dedicated efforts to convene communicators who operate within different institutional contexts but all reach public audiences (directly or indirectly) in their roles. Journalists are not often considered audiences of messaging guidance or narrative work directed to the public health community, and so resources developed by advocates or public health leaders should be tailored to and disseminated to journalists as well. All communicators operate with limited time and financial resources and information overload, so tailoring evidence dissemination strategies to their particular preferences (such as relying on existing, trusted, intermediary organizations) is critical. Additional research to fill these research gaps to support communicators is necessary to support their critical work advancing public understanding of health equity and systemic racism. Communicators serve an important function in shifting narratives and creating the conditions for policy change, and they need more resources and evidence to guide their work.

Acknowledgements

The COMM HSP team expresses gratitude for all the participants who gave their time and expertise so generously to inform the research agenda described in this report. This report was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant # 79754). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

References and Endnotes

- Ponder ML, Kasymova S, Coleman LS, Goodman JM, Smith C. COVID-19 Frames the News: An Examination of Race and Pandemic Frames in Newspaper Coverage. Howard Journal of Communications. 2023:1-17.

- APHA. Racism is a Public Health Crisis. American Public Health Association. https://apha.org/Topics-and-Issues/Racial-Equity/Racism-Declarations.

- Dean LT, Thorpe Jr RJ. What structural racism is (or is not) and how to measure it: clarity for public health and medical researchers. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2022;191(9):1521-1526.

- Confessore, Nicholas. ‘America Is Under Attack’: Inside the Anti-D.E.I. Crusade. The New York Times. January 24, 2024. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/01/20/us/dei-woke-claremont-institute.html.

- Gollust SE, Gansen C, Fowler EF, Moore ST, Nagler RH. Polarized Perspectives on Health Equity: Results from a Nationally Representative Survey on US Public Perceptions of COVID-19 Disparities in 2023. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2024;49(3):403-27

- We used a broad perspective on the concepts of health and racial equity, following CDC’s definition as the “state in which every person has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health.” We were interested in broad dimensions of inequity, including racial inequities but also those determined by social position and other dimensions of marginalization, including sexual and gender minoritized status. Importantly, we did not provide a definition of these concepts for the interview respondents, allowing them to reflect on what these terms meant for them and their professional practice. As a result, there is likely variability in how interviewees were thinking about these core concepts as they showed up in their work. For more on our team’s approach to communicating about health equity, see: https://commhsp.org/areas-of-focus/communicating-about-health-equity/”

Suggested Citation:

Gollust SE, Crane C, Nelson Q, Ford C, Nagler RH. Do these reminders that disparities exist even do anything? A practitioner-grounded research agenda on communication and health equity: Report on listening sessions with four types of communicators in practice. June 2024. Available from: https://commhsp.org/a-practitioner-grounded-research-agenda-on-communication-and-health-equity/.

This report is authored by Sarah Gollust, Carson Crane, Quin Nelson, CeRon Ford and Rebekah Nagler, with graphic design support from Muna Hassan. We acknowledge the full team of the Collaborative on Media Messaging for Health and Social Policy who provided substantive feedback throughout the research process (commhsp.org). This work was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant # 79754). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.